A Masterclass in Creativity

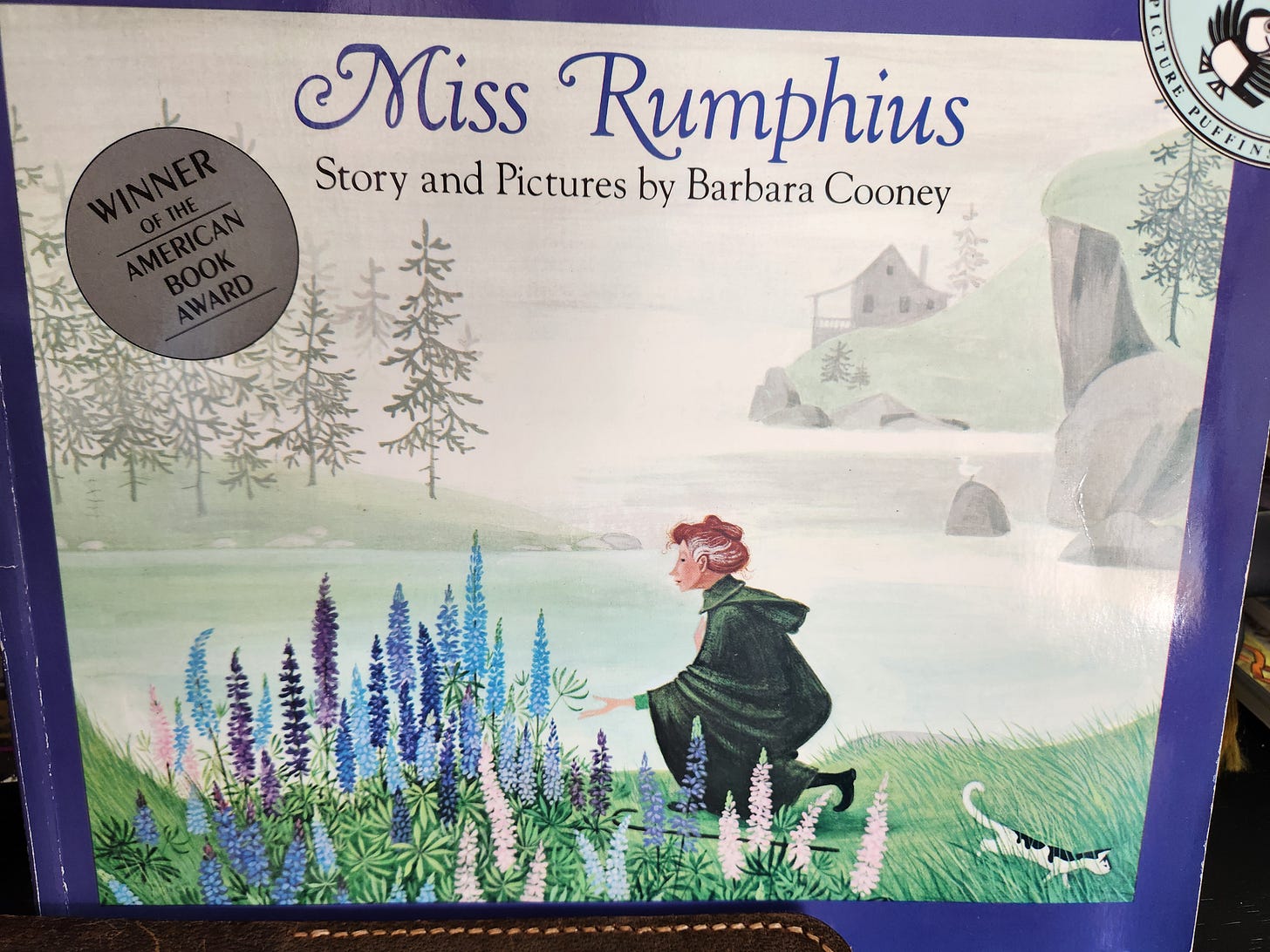

Reading Barbara Cooney's Miss Rumphius

Every year, I teach a unit on Creativity in my AP Language and Composition class. We use the “Creativity Crisis” prompt from 2014 which poses the question: Should there be a class that explicitly teaches creativity in the local school?

The prompt uses a 2010 study on creativity to set up the question. Basically, researchers used the Torrance Test to study the creativity of millions of people world-wide and found that starting in 1990, this “creativity quotient” started going down.

In order to answer the prompt, my AP students debate the topic, read some supplemental texts (including Steal Like an Artist!) and write an essay to our admin on whether our school should have a creativity class.

Also, as part of the unit, I read them two picture books: Frederick by Leo Leoni, and Miss Rumphius by Barbara Cooney.

I consider both to be about creativity, the vocation of the artist, and the nature of learning and work in our society. At some point, I’ll tackle Frederick as a helpful text for those of us who do creative work, but Frederick is also much easier to grok, at first glance, as a text about creativity and art. While I think Frederick has profound things to say, and goes into areas even more primal than creativity and art, I wanted to start with Miss Rumphius because, while it seems like the lessons it teaches are obvious, there’s more going on under the surface than even I realized at first blush.

But having read and discussed it with students for half a dozen years now, I’m finally ready to articulate how the book serves as a masterclass for anyone who wants to do creative work (and if none of what I’m about to write is news to you, then forgive my slow comprehension skills… I always, kinda, sorta knew the wisdom of this book, but it’s only been this most recent reading that unlocked something new for me).

The message may seem simple, but the book lays out more than just a message.

It gives us a map.

First, I’ll lay my cards on the table. I DO think creativity can be taught. Maybe not in the way you (or my students, most often) think about “teaching” or “school” or what-not. Divorce from your mind, for a moment, the idea that modern-day schooling and teaching are the only ways of doing both “schooling” and “teaching.” School, as it is currently constituted in the United States, and teaching, as it is most often approached in said schools, is not what I’m thinking of when I say, “Creativity can be taught.”

Maybe the better statement would be, “Creativity can be cultivated,” or, “Creativity can be nurtured/encouraged/allowed to flourish.”

Saying that creativity can be taught is not the same as saying the only way to be creative is to have someone teach you how. I do think humans are innately creative. Whether that makes me a Rousseauian or whatever, I’ll leave the education theorists to decide. But part of my reason for believing humans are innately creative is because of my belief in God as the creator and humans as beings created in his image. If we are created in his image, then we must have some creative capacity, similar to his own (though obviously different, since we can’t make an entire world and universe out of a void).

This is Tolkien’s idea of the sub-creation, an idea I wholeheartedly subscribe to.

So, humans are innately creative. No need to teach it, then, right?

But that’s a bit like saying humans are born with the capacity to learn language, no need to teach it, right? After all, we don’t really “teach” spoken language in the way most people define “teaching.”

But we do speak to little babies. We do read to them, sing to them, and talk to others in their presence. Humans learn language by hearing other humans speak it. Even though we have an innate capacity to learn language, we still need exposure to it. We need lots of speech to happen around us—sometimes very explicitly—in order to begin speaking ourselves.

My daughter had speech delay as a young child, and in order to facilitate her ability to speak, we had to do a lot of explicit speaking with her. We had to be way more intentional than what’s typical with a young child because she needed extra support. She went to speech classes before preschool. We had to teach her more directly, and now, thank God, she speaks wonderfully (and all the time, lol!). But we had to teach it because it wasn’t happening in the “normal” way.

I see creativity as something similar.

If we get out of the way and let kids do their thang, and if we continue to let children and even adults just do their thang, then maybe we’ll all develop our creativity without any explicit teaching.

But we know that’s not how this world works.

We don’t just get out of the way and let the creativity flow. We set limits and provide structures and we critique and grade and put kids in competition with each other and suck all their time away through organized sports and lessons and homework, and before you know it, I get kids in high school who feel like all the creativity has been leeched out of them.

I’m old school in how I define creativity, by the way. I take it at its word. And that word is “create.” Anyone who makes something is being “creative.” It doesn’t have to be art either. Anyone who makes something, whether it’s a batch of muffins, a wooden chair, or a really cool PowerPoint (I’m sure there’s one out there, somewhere) is being creative.

That’s it.

Did you make something? You’re creative.

But, of course, we want the things we make to have meaning, to matter to us. This is where people see schools and learning as “uncreative.” We have to make things for Teacher, and we often don’t want to make these things, and so we associate making with coercion, school with punishment.

We want to create things that make us happy, that help others, that express our feelings and ideas about the world.

We don’t, unfortunately, do much of that in school.

But just because modern-day schooling isn’t giving us opportunities to create what we want doesn’t mean that we can’t learn how to be more creative, in school or out.

Which brings me back to teaching and learning. Just as my daughter needed help with speech, we often need help with our creativity. We don’t need a teacher to teach us how to be creative so much as we need help on the journey. We need guidance. My daughter COULD learn to speak, but she needed more guidance, more explicit, intentional intervention.

I think we should see our creativity in a similar way. We need more guidance, more explicit intervention.

That may or may not happen in our schools. I’m not the Fairy Queen of U.S. Education and can’t wave my magic wand (oh, how I wish I could wave my magic wand!).

But I do think we can learn from Barbara Cooney in her picture book, Miss Rumphius. I think she gives us the roadmap, the explicit instruction on how we can be creative throughout our lives, not just in childhood.

We have the innate ability, we just need someone to show us the way.

It starts with our narrator (the great-niece of the titular character) telling us about her great-aunt Alice and Alice’s childhood living with her grandfather in a city by the sea.

The grandfather was an artist who made wooden statues and painted pictures. Young Alice helped her grandfather with his work, much like an apprentice, helping him put in clouds or other small details. Her grandfather had traveled to many places before settling down by the sea to make his art.

At one point, she tells him that she wants to travel the world too, and live by the sea when she grows old. But her grandfather tells her she must do one more thing: “You must do something to make the world more beautiful.”

Alice doesn’t know what this will be yet, but she promised him she’ll do it.

She grows up, of course, moves away, and takes a job at a library. She helps people find books and information, and she often goes to the conservatory in town to be in a beautiful garden and experience nature (the book shows her doing this in wintertime with snow on the ground). While in the conservatory, she decides it’s time to travel the world.

And she does. She travels to lots of places and does lots of things (often in nature). She visits an island and meets a man called the Bapa Raja. Curiously, he gives her a conch shell on which he has painted the words, “You will always be in my heart.”

She cherishes her time with him and his family, but must leave eventually, and when she ends up going to a desert country and falls off a camel, she hurts her back so badly she must return home. Her travels come to an end.

She finds a house by the sea and settles there. She spends a quiet life gardening and enjoying the seaside. But her back injury gets worse, and for one whole winter she stays in bed to recover.

As spring arrives, she spots the lupines she planted last season begin to bloom. She loves the sight of them as she convalesces in her bed. They give her joy.

When she’s able to get out of bed, she goes for long walks and sees lupines growing far from where she planted them. She realizes the birds and breeze must have carried some of the seeds to this new place.

An idea strikes her. She knows now how she will make the world more beautiful.

Miss Rumphius begins to sow lupine seeds wherever she goes. All over town. All over the countryside. They don’t grow immediately (no seeds do), but eventually, they sprout and grow and blossom, and when they do, the land is covered in lupines.

While she’s sowing them everywhere, people call her “that crazy old lady,” but eventually, when the flowers color the countryside, filling the town with beauty, they begin to call her the Lupine Lady.

And then we return to our narrator, Miss Rumphius’s great-niece, and all the children who have come to visit the Lupine Lady, the oldest person they’ve ever met, and we see our narrator tell her great-aunt that she wants to travel the world and live by the sea, and of course, Miss Rumphius tells her she must do something else too: “You must do something to make the world more beautiful.”

Our young narrator promises she will, but she does not yet know what it will be.

There it is. The roadmap. The masterclass in creativity. Do you see it?

I didn’t fully see it at first, but over the years as I’ve read this book and talked about it with students, I can see all the landmarks on the map, all the ways we can follow its wisdom without feeling like we’re being restricted or stifled in our own creative journeys.

Young Alice first spends time learning from her grandfather. He mentors her, gives her opportunities to learn about art and craft, and counsels her. Later, at the end, we see Old Alice counsel her great-niece, acting in that same mentorship role as her grandfather once did for her.

This is why I say creativity can be taught. It’s not about formulae or memorization; it’s not about lectures and tests.

It’s relationship. It’s mentorship. It’s guidance and wise council. Alice learns from her grandfather important lessons that help her on her creative journey. The narrator learns from Great-Aunt Alice those same important lessons. Creativity is a lineage. It gets passed down from generation to generation, just as language does.

So that’s step one. We need mentors. They don’t have to be artistic grandfathers or lupine-planting great-aunts—they don’t even have to be literal relatives—but we need those who have come before us to guide the way, to offer wisdom and encouragement. And if it’s members of our family, all the better! We need to see real people living creative lives in our own communities.

Alice’s three promises are significant too. Travel the world, live by the sea, and make something beautiful.

I don’t think we need to take these too literally, but I also don’t think they’re just metaphors either.

1.) Travel the world.

This may be hard for some of us, either because of prior commitments or lack of funds, or maybe even a lack of desire. I know I’m not nearly as travel-happy as so many other folks seem to be. I’m more of a stay-cation gal. Which isn’t to say I’ve never traveled. I’ve been to several places, both overseas and domestically. I live in Michigan too, so going to Canada is basically like going to Ohio (and better, obviously).

But traveling the world should expand your horizons. It should put you in touch with new people, new experiences, new cultures. Even if you can’t or don’t want to travel, curiosity about the world is fuel for your creativity. Learning about the world in all its variety is what’s happening here. Miss Rumphius is having experiences and learning from them.

And it’s significant that so many of her adventures take place in nature (I’ll get back to that later).

But what really resonated with me in this most recent read-through of the book is the episode with the Bapa Raja.

First, this is a meeting with another artist. It’s not articulated this way in the book, but the Bapa Raja IS an artist. He painted a conch shell—he made something—and that act, that making, is all it takes to be a creator. First, her grandfather modeled what it was like to create things, then the Bapa Raja modeled it. Two mentors, two relationships that showed how the creative life is possible.

And it’s significant that he painted a conch shell. Nature inspired him. Nature was part of his art.

Cooney is showing us that creativity flourishes when we allow ourselves to experience and respond to nature. Could the decline in creativity as shown by the Torrance Test be due to our increasingly indoor lives? Why did creativity start to decline in 1990? Is that when parents started sheltering their kids into the house for fear of stranger danger? Is this when we became increasingly captivated by computer screens?

These possibilities are why I see Miss Rumphius’s travels as both metaphorical and literal. We don’t necessarily have to travel the world, but we do need to get out into nature. God’s created world can be inspiration for our sub-creation. The Bapa Raja’s gift shows us this.

And isn’t it interesting that he gives his art as a gift? Another teaching moment from the book. Our creative work is not meant for the marketplace. Sure, we might have to participate in a market economy to survive, and we might have to sell our art as a means of doing that.

But our creative work, in its purest form, is a gift.

2.) Live by the sea

Again, I don’t think this has to be literal, but as artists, as creative people, the connection with nature is vital. Miss Rumphius spends time in the conservatory, in far flung places climbing mountains and exploring deserts, and finally, she settles in a cottage by the sea. Both the settling and the cottage’s location are important. The creative process involves going out and returning home. An exploration of the world and a time for contemplation.

Again, Miss Rumphius’s experiences are meant to be taken both literally and metaphorically. We don’t have to injure our backs and stay bedridden for months in order to have creative breakthroughs, but we do need time: time to think, time to rest, and time to heal. Creativity is born through contemplation.

The exploration—symbolized through Miss Rumphius’s travels—is the first part. We need to see the world, spend time in nature, learn new things, meet mentors and fellow artists (even if we don’t meet them face-to-face, we meet them in their art).

But after this exploration, we need time to think. Time to rest. Time to “winter.” And time, even, to be bored.

Miss Rumphius retires to the sea, and that means she is still close to nature, close to the movement and life that water represents. She’s not able to move all that much (due to her injury), but she’s able to see the natural world through her window. This quiet time, this contemplation, is what allows her to see the lupines growing in the window the following spring.

It’s not that she didn’t know the lupines would grow—she planted them herself! But what was new, what happened as she lay in bed resting and recuperating, was that she saw the lupines with renewed vision. She had changed in those months of healing, those months of “wintering,” and that change within her allowed her to see the lupines in a new way.

After her period of rest, she goes out, and on her travels, she sees that the lupines that started in her garden had spread to other far-flung places. This is the moment of her creative breakthrough, where she realizes what she can do to make the world more beautiful. It happens only because she has had time to contemplate, to rest, to think, to be bored even, and to see with new eyes.

This is the second lesson in creativity. We need rest. We need boredom. We need time to think and let ideas gestate. We need to “retire” to a place that keeps us in touch with the natural world. And we need to (again) spend time in nature. It’s on a walk that Miss Rumphius find inspiration. I don’t think this is a metaphor. Walking literally helps us have ideas and breakthroughs.

We don’t have to “teach” creativity like we’d teach algebra, but we can certainly cultivate habits like walking and resting and contemplating as part of the creative process. We can model these habits for students. And we can invite students to participate in these habits as part of their education.

3.) Do something to make the world more beautiful

I think the key word here is not “beautiful” but “do.” Creativity’s root is the verb “create.” Creativity is the noun, but “create” is the verb, and that’s also what “do” is. A verb. An action.

And the second most important word in this line is “make.” You must MAKE the world more beautiful.

We can’t really make in the way God can make. We can’t make ex nihilo, from nothing. Our making must start with what’s already been made and make new things from it. We can do this in so many ways, and most of them are not what we traditionally think of when we think of “creativity.” But that’s exactly why the line is a wise teaching for the student of creativity. Part of the lesson in learning how to be more creative is to see things in a new way. Miss Rumphius’s creative act gives us a new, more creative understanding of creativity itself.

Creativity is not “the arts.” Artists are creative, yes, but so are bakers and knitters and carpenters. Anything that involves making stuff is creative. It’s not the exclusive realm of The Artists. (And hint: everyone is an artist; we give up a lot of ourselves when we think artists are some special club to which we don’t belong.)

Miss Rumphius doesn’t paint pictures or carve wooden statues. She doesn’t even paint a conch shell. She plants lupines, spreading them far and wide. One of the book’s greatest lessons in creativity is to help us see that our idea of what “creativity” is is limited.

If we are to be more creative, we must do more making. It’s as simple and as hard as that. Miss Rumphius plants seeds. Not difficult. But not something that happens without her participation. The seeds might have spread from beneath her window to the far-flung paths via birds and wind, but to really paint the countryside with lupines, Miss Rumphius has to get out there and do it.

At first, she is called “that crazy old lady.” Instructive. When we start our doing, when we begin our making, we may be called crazy. We may get funny looks. We may not get noticed at all, but in our minds we’re worried others are judging us. The hardest part of the making isn’t the making itself; it’s the fear that keeps us from starting. From doing.

We can see the creative life modeled, we can travel and soak up nature, we can get gifts and feel the tug to give gifts in return, and we can contemplate and walk till the cows come home, but the third thing we must do is DO something. We must make something.

Yes, it’s the “beautiful” part that stops us.

What if what I make isn’t beautiful? What if it doesn’t add to the world? What if it’s no good?

We don’t yet know how to make the world more beautiful, and that’s what stops us from doing it.

This is where all the other lessons from the book come back to help us. Alice’s grandfather painted paintings. Alice liked them. She helped put in the clouds.

The gardens and the library were things she liked too. And her travels around the world.

The gift from the Bapa Raja was also a thing she cherished.

She planted the lupines because she liked them.

And when she saw them again, out along the pathways, she knew how happy they made her.

Making the world more beautiful is as simple as acknowledging the things we like—the things we think are beautiful—and using those things as our inspiration.

Alice’s love of nature is there from the start. We see it in every phase of her life. Is it any wonder that her act of creativity is an act that participates with nature?

What we love is what we make. That’s the secret.

And if we love what we make, if we do it for the joy of making and no other reason, then it doesn’t matter who calls us “crazy.”

This isn’t a selfish act either, a kind of “I’m gonna do my art whether you like it or not!” thing. Just as her grandfather did by mentoring her, and the Bapa Raja did with his conch shell, Miss Rumphius’s creative act is a gift. She doesn’t keep it to herself but spreads it far and wide for others to enjoy.

This is part of the lesson in creativity. We do it as a way to “make the world more beautiful.” We do the making so that others might share in it. This is why “do” and “make” are the key words: the world doesn’t get more beautiful if we don’t DO something. We must act. Learning, seeing, thinking, and walking aren’t enough. We must eventually do the thing. The making.

And then, when we have made our things, when we have put our creative efforts into the world, we continue the cycle. We teach others. We share our gifts.

Remember: Miss Rumphius becomes the teacher and mentor to the next generation, the next student. Her great-niece is inspired by her. And Miss Rumphius does the same as her grandfather did before her: she tells her great-niece to do that third thing, that most important thing, that making and doing, that creative act.

She’s teaching her great-niece how to be creative. Just as her grandfather did. Just as the Bapa Raja did. Just as Barbara Cooney did.

Creativity can’t be taught like we teach grammar or arithmetic. But it can be taught.

And Miss Rumphius is our masterclass.

It’s no Miss Rumphius, but I do have a new collection of short stories you can read called Dark Was the Morning and Other Stories. These are seven strange tales of various type: some weird fantasy, some old school dragon-y fantasy, some fairy tale fantasy, and a Merlin’s Last Magic prequel story about Merlin’s time in Atlantis. It’s available in ebook and paperback from all the usual retailers.

And check out my other books (if you haven’t already):

The Thirteen Treasures of Britain (if you are looking for Arthurian fantasy)

Avalon Summer (if you want a dash of nostalgic coming-of-age, 1990s-style)

Gates to Illvelion (if you want a strange fantasy meant to evoke the style of Appendix N fairy-tales like The Last Unicorn or The King of Elfland’s Daughter)

(And have I mentioned that the main character of Avalon Summer, Sarah, finds and reads Gates to Illvelion and sees strange parallels between that book and her own life? Well, she does, and it’s weird!)

That’s it for now! Thanks so much for reading!

Remember, if you enjoyed this post but can’t afford a monthly subscription, you can always buy me a coffee.

This newsletter is run on a patron model. If you can support it with a paid subscription, I would be grateful.

As always, this newsletter remains free and open to all who want to join me in exploring the various contours of the fantasy genre. Thank you to ALL my subscribers!