I’m challenging myself to send out two newsletters per month in the hopes that such a lofty goal (for me anyway) might spur more writing and increase my creative production overall. Making stuff leads to making stuff.

I’ve started writing the beginnings of a couple of essays, but they aren’t finished, so for my second newsletter of July, I’m dipping into my fiction files and sharing a short story called “Salt Kisses.” It’s about a girl named Aoife who believes she’s a “daughter of the sea” and not the natural daughter of her parents. This belief will lead to events both tragic and wondrous.

Maybe you’re vacationing by the sea right now, or sitting by the poolside. Or maybe you’re stuck in the office (in which case, my sympathies). But wherever you are, I hope this story will give you a whiff of the salty sea air and a longing for something beyond the horizon.

If you’d prefer to read it on your kindle or e-reader, download the file HERE.

Enjoy!

I.

Aoife knew she was adopted and never tired of telling her parents so.

“You’re not adopted,” her mother would sigh, pushing a grayish auburn hair from her tired forehead. “I think I would know.”

But Aoife ignored these obvious protestations, jutting her chin in defiance of what her mother had said.

Her mother was a liar, that much was plain. It was clear to anyone that Aoife could not be the daughter of this woman. Her mother hardly ever cried or looked off into the distance; she never felt the lure of the horizon and what must lay over it. Her mother’s horizon was the edge of the threadbare rug, the sea-salt grime on the window panes, the cooking pot that always needed scrubbing.

Aoife was the daughter of the sea. Her mother was all dry land.

“You’re getting on my nerves,” Mother would reply and then hand Aoife a broom.

Their shabby tin house was always letting in the draft and the pungent, salty stench of rotten seaweed and fish from the docks. It took Aoife’s mother most of the daylight hours to drive out the sea smells. A waste of time, really. They’d just come back inside the next day. Aoife claimed she liked those smells anyway. The lure of the sea, she’d say.

“Try the lure of the front stoop,” Mother would reply. “It needs sweeping.”

Aoife would scowl, snatch the broom away, and stomp outside. She refused to sweep, staring instead over the thatched and shingled roofs of their street to the tall masts of the ships beyond. Like flags calling her home, their sails billowed as they set off into the blue-gray water.

“You shouldn’t talk that way to Mother,” Aoife’s older sister, Ellen, would lecture. Tall and lithe, Ellen might have been beautiful if her oval-shaped face hadn’t gotten scarred from the pox. “Your words are like wounds. They cut her to the heart.”

“Don’t be such a stuffy prim,” Aoife would hiss back. “It’s clear as day I’m not her daughter.”

The two girls were as opposite as could be. Ellen was quiet, always proper, never bold. Aoife raged like a squall anytime she didn’t get her way. While Ellen did all she could to help their family—taking work in taverns or sewing nets with the old women in town—Aoife spent most of her time by the docks and the rocky shoreline, daydreaming.

“You’ll be the death of her, Aoife. Is that what you want?”

“What do I care? She’s been a wet nurse, nothing more.”

These arguments were the only time Ellen showed any strong emotions; most of the time she was measured and demure. But when Aoife took after their mother like this, Ellen revealed a wave of steaming hot anger that could boil the clothes clean. It was clear what Ellen thought of her sister. Aoife was an ungrateful, wicked brat, undeserving of the great sacrifices and affections their parents showered upon her.

Aoife, for her part, thought Ellen was an insufferable prig.

The weather had been coming for days, but Aoife paid no mind. She could withstand a storm, any storm, for she was born of the sea and had no reason to fear.

“Get home, child!” the grizzled men tying up boats would call. “Storm’s a’coming!”

Aoife didn’t care. Let the storm take me, she thought. Anything was better than life in this salt-dried, rock-hewn village.

The trouble started at school, in the yard before the morning bell. The girls were swarming. Aoife never gave them any courtesy, but today was different. Today, she had the audacity to ignore them completely. She was deep in a daydream, wondering about the very depths of the sea. She saw the eye of a giant squid and didn’t notice Catherine O’Connor calling her name.

“Heard a rumor said your feet are covered in scales!”

Aoife didn’t reply—not out of rudeness or even shame—but simply because she was swimming in choppy waters with the selkies. Plugged with salt water, Aoife’s ears couldn’t hear the Catherine O’Connors of the world.

“Why don’t you go jump in the sea!” Catherine yelled.

“Drown yourself and save us from having to look at you!” the other girls called out.

Laughter, tart and sharp. Laughter ringing in Aoife’s ears, even through the deep waters. Laughter that shook the daydream out like sand from a shell.

The squall raged then and stopped Catherine O’Connor’s laughing. Aoife, unfortunately, got sent home by the schoolmaster.

“There’ll be your salt kisses again,” her father teased when she got home and recounted the injustice done to her. “Daughter of the sea.”

“Salt kisses?” Aoife shoved a lock of hair behind her ear.

“Aye, your tears. As salty as the brine on the boat hull. They kiss your face to soothe ye. The sea being your natural parent, o’ course.”

Aoife didn’t think it fair that her father teased her while she was crying. Her parents never showed any tears. They were as dry as bones. Another reason why they weren’t her family.

“What did the girls say?” her mother asked, trying to be gentle.

“They asked about her feet,” Ellen answered when Aoife refused.

Mother scoffed. “No shame in that. Isn’t your fault you had the pox.” She said it to Aoife, but her eyes glanced at Ellen.

“It’s not from the pox!” Aoife raged. “I’ve told you! They’re—”

“Hush now,” Mother said, standing up and going back to the stove. “I’ll have no more of that.”

Aoife knew it bothered her mother when she mentioned her true parentage, when she insisted on speaking the truth. But Aoife wasn’t going to back down.

“You have no claim on me!” Aoife cried. “I am not your daughter!”

“Aoife, you shouldn’t now—“ her father began, but his words were too weak. As usual.

“Hush.” Her mother didn’t even turn around. She turned the handle of the spoon in the pot. “Set the table, why don’t you? Be useful while you scream.”

Aoife grunted and stamped her foot, and before she could even think, she was out of the house. She barely noticed the gathering clouds or the wetness in the air. When she stood by the docks, the old men tying their boats gave her grim looks.

“Be off, young one!” they called to her. “Can’t you see what’s coming?”

Aoife stared at the waves coming in, all choppy and gray. The sea was cold. She searched the depths for some sign of life, for something to welcome her, but nothing came. In the distance, boats could be seen coming in, trying to get to shore before the worst of the wind howled.

Sitting on the peer, Aoife put her foot across her leg and started unfastening the shoelaces. The shoe came off then the stocking. Her bare foot was exposed to the salty air.

“These are my true feet,” she said defiantly.

The skin was dappled with gray spots in a pattern that resembled fish scales. To Aoife, these spots were the remnants of her oceanic origin. They were her body’s way of regaining its birthright. They were decidedly not scars from the pox.

She thought of how her feet must have been when she was born. Like the fins of a fish, they must have glimmered. Silver and shimmery, they must have reflected all the colors of the rainbow when the light streamed down through the water.

Now they were a drab gray. Dried out by too much time on land. Aoife wondered if she should dip them into the salt water.

Rain started to sprinkle, blurring the gap between the sea and the sky. Everything was a hazy gray. Aoife stood on the peer, bare feet soaking in the rain. The waves rolled higher and higher as the wind pushed them into crashing swells. The fishermen who had been coming into shore as fast as they could were gone now, hidden somewhere behind the waves and rain or else lucky enough to have reached the docks further down the coast.

Aoife put her face to the stinging rain and looked out as far as she could. Her own tears mixed with the sky’s. This is my home, she thought. My fierce, endless, wild home!

How could her father have given all this up and sold his boat? How could her mother have settled for hanging other peoples’ dingy washings and scrubbing floors? The answer was clear. They were not her parents. Her feet were a sign… She belonged to the sea…

“Aoife!” It was Ellen, coming up the road, heading toward the peer. She was wrapped in an old shawl, one of Mother’s dark blue ones, knitted on winter nights when the wind bit at the door. It made Ellen look like a banshee, her long, oval face peeking through the dark shawl, her pocked cheeks all sunken by the storm’s shadows. “Come away from there!”

The sound of her sister’s voice startled her. Aoife turned, her bare feet slipping on the mucky wood, her balance lost.

“Aoife!”

The water hit Aoife’s body with a sharp force, and before she knew what was happening, she was submerged. It was like a block of ice had formed all around her. The water was so cold it burned her skin. She had but one thought: I am drowning.

All ideas about being born of the sea vanished. For Aoife, water now meant death. She struggled to find her way up to the surface, but every way she went led further into the depths. Her lungs started to burn even as her muscles weakened. Everything was so cold, so dark. Her pockmarked feet couldn’t help her. They didn’t rescue her or transform into fins or do any of the other things she had dreamed of. A terrifying thought overcame her, like a voice calling from the depths.

Stop moving. Stop fighting. Just sink.

Her long red hair drifted around her like seaweed. The storm waves rocked her body back and forth like a baby in a cradle. She had never given up before, but something about it felt effortless, as if it were the most natural thing in the world to let the waves and the water take her down, down, down. It felt good to give in, to let go.

Ellen’s hands grabbed her under the arms and yanked her up. With more strength than Aoife realized her willowy sister had, Ellen pulled her to the surface. Gasping and sputtering, Ellen pulled Aoife close to her in a tight embrace.

“Can you swim?” she cried over the sound of the pouring rain.

Spitting water out of her throat, Aoife could barely talk. She wanted to nod her head “yes,” to be strong again and swim to shore, but she couldn’t. She had no strength left.

“Hold on!” Ellen commanded then hoisted Aoife onto her back. She tried to swim and carry Aoife at the same time, but the weight was too much. The sea began to claim them both. “Aoife, I can’t!” Ellen’s voice was panicked. She started to struggle against the pull of the waves, started to sink too. Aoife closed her eyes and thought again of how easy it would be to stop fighting.

“Ahoy! We’re comin’ for ye, girls!” The grizzled voice of the fisherman could be heard high above the din of the storm. His was a voice that had wailed over many a squall. The boat rocked and crashed its way over the choppy waters until it came close enough for the crew to throw out a net.

When the net splashed into the water, something awoke in Aoife. Fury seized her. Fury against the storm, against the waves, against the sea that wanted to sink her. She was resurrected out of the dark waters, eyes ablaze. Entwining her fingers into the netting, she began to swim again. They heaved her over and up and pulled her onto the boat.

But when they flung the net out again for Ellen, their faces grimaced. The girl was gone.

Aoife didn’t know what was happening. She heard voices shouting into the wind, but she couldn’t make out what they said. All she knew was there was a heavy jacket suddenly draped over her shoulders, and she was shivering, and she wanted to sink into the musty-smelling jacket and go to sleep. But she heard the shouting, and the rain battering down onto the fishing boat’s deck, and she wondered where Ellen was, and why she wasn’t sitting there next to her, wrapped in the jacket too.

“We lost her.” She heard someone say it. It sounded like it came from within her head, but it must have come from one of the men. It was so soft, though… So near…

Aoife didn’t remember much after the boat started in toward shore. She was too cold, too tired to think or hear properly. There were words said above the din, grim faces peering out from beneath soaked caps, but nothing felt real. Aoife simply sank into the heavy jacket and waited. She didn’t care how weak it made her feel: She wanted her mother.

II.

The house had turned quiet. No one spoke anymore.

Aoife wished her mother or father would speak, would yell or blame or cry out to heaven. Instead, they said nothing. It was like Aoife had turned invisible. As if two daughters had drowned in the sea instead of one.

She had no right to complain, though. Aoife hardly spoke herself.

In the schoolyard, she had lost her saltiness. Her stormy squalls had dried up. When the other children passed by, they avoided her, casting furtive glances at her sad figure: a piece of driftwood cast out of the sea. There were no more taunts or teases from the Catherine O’Connors of the world. Only whispers and unwelcome pity.

At first Aoife said nothing. She stayed quiet in the house and at school and wherever she went. She was afraid to speak for fear that tears would come. She no longer wanted to feel the sting of salt kisses or anything else.

After three weeks of such silence, Aoife came home from school one day and found the kitchen empty. She half-expected Ellen to be there stoking the fire or helping Mother mend some nets, but the house was dark with late-afternoon shadows instead.

Aoife didn’t bother to light the lamps, nor rekindle the cold stove. Wherever her mother might be, Aoife didn’t know, but she picked up a broom and tried to ignore the silence as best she could. She moved the handle distractedly, barely looking at the trails of dust she shuffled back and forth.

The front door creaked on its hinges and then stopped. Aoife froze, broom in mid-sweep. She expected her mother to come in, and the thought of it made her body clench. They never fought anymore, not since that day… but her mother’s silence was worse than any fight. It was an accusation. A judgment. And Aoife knew her guilt.

Instead of her mother, fingers scratched the wood and an old voice croaked after them.

“Mari?” said the voice, like rusted hinges.

“She’s not home,” Aoife answered back, “she’s—”

The door swung open. A hunched woman wearing a faded red robe shuffled into the room. She wore a silken scarf in motley colors over her head, framing her sunken face and making her eyes and nose stand out. Her eyes were wide and unblinking like an owl’s; her nose, bulbous like a radish and just as red. Her cheeks too, though hollow, were tinged crimson. Father had said red cheeks and nose were a sign of those who took too much drink and didn’t know when to stop.

The old woman tottered closer, and Aoife stepped back, the broom held in front of her like a quarterstaff.

“I ain’t here to hurt ye, dear,” said the woman. “I’m looking for yer mam. Mari Sleeth. Do ye know where she might be?”

Aoife shook her head.

“Not hiding is she?” The old woman raised her thin eyebrows and cocked her head to look around Aoife.

“No,” said Aoife. “She’s not home. I told you that.”

The woman smiled, and a gold tooth glinted in her mouth. “That ye did.”

“I can take a message for her.”

The woman leaned towards Aoife and squinted. “You’re the daughter, all right. It’s good yer mam has you, little one. She deserves that much.”

“I’m not the only daughter,” Aoife snapped. Her voice surprised her.

“Aren’t you, then?” The woman stared hard at Aoife. Her large, unblinking eyes made the girl flinch, and all the snap went out of Aoife in an instant. She looked down at the broom bristles.

“I’m the only daughter now.” The words caught in Aoife’s throat.

“No shame in that,” the woman croaked. “Not yer fault the other’s drowned.”

Aoife felt heat rise to her face. What right had this strange woman to speak so bluntly? They never spoke of Ellen that way, never mentioned her—

“I best be going,” the woman said, lurching her hunched body around toward the door. “Give your mam the message. Tell her Ol’ Janny’s been calling and come to see me soon.”

“Old Janny?”

“We go way back, yer mam and me. More than fifteen years.” Her gold tooth flashed. “Tell her to come soon. Don’t forget, child. I’ll know if you do.”

And with that, Old Janny hobbled out.

III.

They ate in silence. Mother hardly looked at Aoife, and Aoife wasn’t sure if she was glad for it or not. Father sipped his beer and stared at the edge of the table. Aoife was the only one who seemed to have anything waiting on her lips, but her courage had deserted her as soon as they sat down to eat. The leek soup tasted thin and bland in her mouth.

Mother sighed and pushed her chair out, getting up to clear the table.

“I—” Aoife began, but her mother’s tired face stopped her.

“Something to say, love?” her father said, his voice flat. He didn’t look at her.

Aoife swallowed hard. “There was a visitor today.”

“A visitor?” her mother said. Not a hint of curiosity, just the words. Her mother picked up the bowls and carried them to the sink.

“Yes, an old woman.” Aoife thought of Old Janny and the hint of a threat behind her parting words. “Called herself Old Janny and asked after you, Mother.”

The bowls crashed into the sink. Mother coughed and tried to make it look as if she’d meant to drop them. She took to scrubbing them furiously.

“Who now?” Father asked, his eyebrows drawing together in confusion.

“No one,” Mother said quickly. “A beggar woman, I’m sure. They come after me sometimes when I’m out to market, looking for coin.”

“Didn’t know you were so generous,” Father said.

“She said you’ve known each other for fifteen years,” said Aoife, not letting her mother off the hook.

“And were her cheeks flushed too?” demanded Mother. “A drunkard telling tales, that’s all.” She scrubbed harder.

“She said to come see her soon.”

“I’ll do no such thing.”

“But she said—”

“Aoife, enough.” Her mother’s voice was sharp and final.

Father slid his chair back and went to find his pipe on the wooden shelf across the room, leaving Aoife to sit alone at the rough-hewn table. The thick blue tablecloth was laid bare in front of her and the sounds of her mother’s scrubbing were the only noises to be heard. Aoife sat adrift at the table, an anger welling inside, and guilt too, for she wanted to argue with her mother, but she couldn’t. Not now. Not ever again. She was the only daughter. She had no right to press a knife into her mother’s heart again.

No shame in that. Old Janny’s words haunted her as she lay in her cold bed that night. Not yer fault the other’s drowned.

Her legs were getting too long for her burlap blanket, and her toes peeked out into the frosty October air. Aoife stared at her scarred feet. She could barely see the gray spots in the dark, but she knew they were there. They were ugly feet and ugly scars. No mermaid scales. Just dingy, crusted marks from the pox. Aoife squeezed her eyes shut and cursed herself for ever thinking otherwise.

Tomorrow, she’d go to the docks and find work. Maybe she could start mending nets or offer to wash the dishes at the Busted Cork for pennies a day. She’d pull her weight. No more pretending she wasn’t what she was. No more daughter of the sea.

She had been all set to go to the docks the next morning, but when her mother had silently put on her shawl and slipped out the front door just before dawn, Aoife changed her plans and followed after. Her mother headed toward a cramped and crooked street wedged into the south part of the village. A dingy street, filled with tilted shacks and weather-worn tents, it was the poorest part of town. Aoife’s family was not well-off, not by any means, but even her mother would balk at coming to this hopeless slum without good reason.

The reason hung above the doorway of a squat hut. A wooden sign, flaking with old paint, marked with the sign of two huge, round eyes.

Old Janny.

Aoife’s mother went in.

Aoife herself wanted to go in too, but how could she? She waited several yards away, half hidden by a string of rags hanging out to dry in the cool early morning air. The dull rags of brown and gray flapped lightly in the breeze, and Aoife moved this way and that to stay behind their cover, out of sight. She somehow felt that Old Janny, with her owlish eyes, could see through the walls of her hut and spy intruders. But Aoife’s curiosity was growing stronger than her apprehension, and when there was no sign of anyone else in that crooked street, she slipped through the folds of hanging laundry and approached the hut.

There were no windows, and the thatched straw door was shut. But the hut was rickety, built of uneven bits of tin and pine, all stuck together with odd-shaped nails, and there were a few small gaps in the walls, slits just big enough for a small eye to peek through. Aoife circled round the back of the hut and found a peephole just eye-level. She could hardly see inside, for the one-room hut was dark and lit only by candles, and some kind of spiced smoke burned from a brazier in the center of the circular room. The scent of the smoke gave off faint traces of cloves, but it reminded Aoife of stale water that had sat out for too many days.

Her mother was inside, and so was Old Janny, and they sat near each other around the brazier, but Aoife couldn’t see much else and swore under her breath that she was stuck outside. She hadn’t put on a coat or a shawl, and the breeze was starting to pick up. The sky was heavy with gray clouds that hung low and looked ready to burst.

Aoife put her ear to the slit in the wall and listened, plugging her other ear to keep the wind out. Old Janny started to speak, but Aoife’s mother cut her off.

“You had no right to come to my house,” Mother said, quick to anger.

“Don’t think I haven’t seen you walking sea-way, Mari,” Old Janny answered. She wasn’t put off by Mother’s tone. There was a prying quality to Old Janny’s manner, a fingernail digging out dirt from a windowsill.

“And speaking to my daughter.” Aoife’s mother ignored Old Janny’s mention of the sea.

“Aye, your only daughter now. ’Tis a blessing you had two, now that one is gone down to the depths.”

“Never mention my children again. And never bother us with your prying. What business is it of yours if I go to the seashore?”

“No business. Certainly no business.” The way Old Janny said it reminded Aoife of the fishmongers in the market, always trying to entice a customer. “You may wander that way if you wish.”

There was silence, and it lasted a long time. Aoife peeked her eye in again to see if her mother had left.

The two women stood facing each other, smoke slithering around them in long, winding streams.

At last, Aoife’s mother said in a low voice, “Can you reverse it?”

Aoife watched as Old Janny grinned, her sunken cheeks stretching like a vulture spreading its wings.

“Reverse it?” Old Janny reached into the folds of her threadbare robe. She pulled out a heavy pouch that jangled with coins. “Can ye pay the price, Mari?”

At first, Mother’s head hung down. Aoife knew what she must be thinking. What money did they have?

But then her mother nodded and said, “I’ll pay it. If you promise me it will work.”

“Can’t make such a promise. The sea is its own master.”

“Don’t tell me about the sea,” Aoife’s mother snapped. “I’m well-acquainted with her.”

“That you are,” Old Janny said with a curl of her lip. “That you are.”

“What’s the price?”

Old Janny cocked a thin, gray eyebrow. “Same as before. Always the same.”

Aoife’s mother sighed and lifted her wrist, turning it so that the veins faced upward.

Old Janny untied the heavy pouch and reached inside. Aoife expected a coin, but instead, the old woman pulled out a barbed fishing hook.

Aoife’s mother turned away, squeezing her eyes shut. With one swift motion, Old Janny scratched the hook across Mother’s upturned wrist, tearing apart the thin flesh. Blood sprayed out, and Old Janny caught it with a small copper bowl. Then she handed Mother a frayed brown rag and waited for her to staunch the bleeding.

“Now I’ve paid,” said Aoife’s mother. “Give me my due.”

“You talk as if I’ve crossed you. I never did nothing but give you what you asked for. Only what you asked for, Mari. I never held back.”

“You said they’d inherit my blood, you said—”

“I said ’tis likely they’d inherit it. Never promised. Old Janny never promised.”

“But why didn’t they? Why scoop my blood into your bowl if there’s no power left?”

Old Janny grinned. “There is. I can smell it.” She lifted the copper bowl to her round nose and breathed in the scent of the blood.

“Give me my due.” Mother’s jaw was set and her chin jutted out, and Aoife couldn’t help but recognize the expression that once had come so easily to her own face.

“I knew you’d come to me, Mari. I knew you’d try your luck. But whether the sea listens or no, don’t return to me with regrets. I make no promises for good or for ill.”

“Give me what I’ve paid for.”

Old Janny shuffled to a dark corner of the hut, and Aoife couldn’t see what she reached for. When she turned around, she carried something wrapped in a thick piece of burlap.

“You know the steps, aye? But salt water this time, Mari. Salt water, not fresh.”

Aoife watched her mother take the small bundle from Old Janny, but before she turned to leave, she faced the old woman again. Even through the darkness and the smoke, Aoife could see the defiance in her mother’s eyes.

“What good is my blood? What power does it have?”

Old Janny’s golden teeth gleamed in the candlelight, her eyes like two lanterns. “How can ye ask me that? You of all women should know the power of the sea.”

Old Janny sat by the smoking brazier, holding the bronze bowl in her lap, victory in her smile.

The wind flapped against the rags on the clothesline, startling Aoife. Pelts of hard rain were falling now, biting against her skin. She wiped water from her eyes and look again through the slit.

Her mother was gone.

The storm rolled in, clouds as dark as tar overhead. Aoife had to hurry. Already the waves might be too high.

When she got to the beach, the burlap cloth lay in the sand, sodden with rainwater. Her mother stood at the shoreline, a clam shell in her hand.

“Go back, Aoife!” she called without turning around.

The wind and the waves were so loud, Aoife knew her mother couldn’t have heard her coming. And yet she knew.

“Stoke the fire and sweep the floors! This is no place for you!”

“Mother, wait!”

But her mother didn’t wait. She waded into the choppy waters, the shell gripped tightly in her palm. When she was waist deep and the waves were spraying foam into her face, Aoife’s mother reached down with the clam shell and scooped up a draught of water. Then she lifted the shell to her lips and drank.

Aoife expected her mother to gag on the saltiness, but what she didn’t expect was for her mother to convulse and shake all over, writhing like a struck snake. And when her mother sloughed off her clothes in one violent motion, the skin beneath wasn’t pinkish human flesh, but iridescent scales that glimmered in the rain. Scales and webbed hands.

Her mother dove into the water. Disappeared into the depths. The clam shell was tossed atop the waves like a lost dinghy.

Aoife didn’t know what to do, but she crashed into the water anyway. Before any thought came, she grabbed the shell and scooped up a draught of sea water. She drank it, and the salt was like fire in her throat. It made every inch of her flesh shake. The waves were rising, jostling her to and fro, but she stood her ground as the water swelled over her waist. She waited for something to happen, for whatever spell Old Janny had put into the shell to work on her just as it had worked on her mother.

But nothing happened except her stomach felt sour and her throat still burned.

Then a voice from another storm sang into her head. A voice she had listened to once before.

Stop moving. Stop fighting. Just sink.

Her body felt as heavy as one of her mother’s cast iron pots. There was no spell to rescue her, no transformation to take place. Just grief as powerful as an anchor.

Aoife gave in to the voice and let her body sink. She wanted her mother, and somehow her mother was down in the depths of the sea.

She sank beneath the surface, cold water covering her head, while her red hair floated all around her like willowy strands on a dorsal fin. Her body was a stone, dropping down and down into water with accelerating speed. She kept her eyes open, but the water was murky, and soon even the dim light from the stormy sky was gone, and she was surrounded by darkness.

A voice spoke out of that darkness.

“I’m back, Mother.”

It was her own mother’s voice. She was speaking to someone, but who it was, Aoife couldn’t tell. And Aoife couldn’t explain why her mother’s voice sounded so clear under the water, or why neither of them had yet drowned. They were fathoms deep. But all around her the water squeezed like a vice, and everything was black as night.

No human voice spoke in reply to Aoife’s mother, but there was a sound, a long whining sound that reminded Aoife of a creaking staircase, but more melodic somehow, and melancholy. She strained to hear it, to see if some sense came from it.

“You had no right, Mother,” Aoife’s mother continued. “No right to take her from me.”

What right had you to leave?

It was the creaking moan. Aoife could understand it now, though the sound had never changed. It felt almost like the thoughts in her head were speaking through that moan. It sounded like the voice that had told her to sink.

“I wasn’t meant for the sea,” replied Aoife’s mother. “The surface called to me, so I went.”

And left me behind. All these years.

“That’s not what I wanted. I never meant to hurt you. But we’re different, you and I.”

Not so different. We both want back what we’ve lost.

“Will you return her? To dry land?”

I will keep her safe.

“No, that’s not good enough for me.” Aoife’s mother had steel in her voice. “I’ve reversed the spell. You can have me again. See my scales and fins? I’ve given up. Keep me in your depths now. Only let my child have her chance. Let her break the surface and breathe again.”

Why must she go? Why must any of you? You are daughters of the sea. Just look.

Aoife felt a swirl of bubbles cyclone around her, tickling her skin. She waved her arms and legs at the sensation.

She has your blood. They both do.

“What?” Her mother’s voice drew nearer. “Oh, Aoife!”

Aoife felt cold, scaly arms wrap themselves around her, and two blue-gray eyes glinted in front of her. She couldn’t see much more than the eyes, but she knew them.

“I told you to go home!” Her mother’s eyes were flecked with fear, not fury. “Why must you be so stubborn!”

She turned away but kept hold of Aoife’s hand. Aoife could feel the webbed flesh between her mother’s fingers and the slimy scales on her hand. It reminded her of all the times she had to clean the fish her father had brought home in his nets.

“I’ll stay,” Aoife’s mother said to the sea. “Only let my daughters go.”

Aoife wanted to speak, to stop her mother from making this bargain. But would her voice even make a sound? What could she say to either her mother or the sea? Aoife felt small in that vast darkness.

You mustn’t stay in these waters. You must go far away.

“I’ll do it.”

And you mustn’t ever go to the surface again.

“I swear it.”

You are a child of the sea, and the sea is where you’ll stay.

“I’ll pay any price.”

Aoife couldn’t bear it any longer. She opened her mouth to speak and felt the water rush in. But instead of drowning, she breathed the water. The salt didn’t sting her throat anymore. And when it filled her lungs, it made her feel like she’d just gulped the freshest air. She found her voice.

“Mother, you can’t do this!” she cried. “You can’t leave us!”

Her eyes adjusted to the darkness now, and she could see the outlines of rocks and strange fish all around her. And her mother’s body, the fullness of its transformation. She still had a human shape, but instead of skin, she had oily scales that shifted in color from black to green to purple, and her feet were like two fins and her hands were webbed. Her hair was gone—that auburn hair so much like Aoife’s—and her face was flattened and smooth, no more contour of nose or cheek or chin. The only thing that looked like the mother Aoife had known were her eyes, still blue and human and sad.

“I’m giving you Ellen,” her mother answered. “To brighten your father’s heart and mend it. And you will have a sister again.”

Here is the child, said the sea.

Something long and shale gray floated out from the distance, slowly coming into view as it drifted toward them. It looked like a piece of shipwreck, covered in barnacles, but it had a shape and contour that was unmistakably human. As the figure drifted by, Aoife’s mother reached out her webbed hand and brushed against it. It was a tender stroke, but Aoife watched her mother’s eyes flash angrily as she saw what her daughter had become.

“You said she was safe!” her mother screamed. “You said she had my blood!”

And so she does. Your blood is the only thing keeping her alive. What happens to her on dry land is no concern of mine.

“I’m going up.” Aoife’s mother reached out and took Ellen into her scaly arms. The girl’s eyes were closed, and her barnacled form looked to Aoife like a wooden maiden carved into the prow of a ship.

That was not what you promised.

“Nor is this part of our bargain,” their mother said, holding Ellen’s sleeping body close to her. “I said it once before, and I’ll say it again. You have no claim on me. I’ll go where I will and you cannot stop me.”

The sea is its own master.

Currents began to flow on either side of them. Then the currents bent toward each other, and like two snakes eating their tails, they formed a ring around them. Aoife could feel herself getting sucked down by the force of the whirlpool, and her mother too was struggling against it. Somehow she managed to grab Aoife’s hand, and though no words passed between them, they knew what they must do. With every last ounce of her strength, Aoife kicked her legs and willed her body to float toward the surface. She fought against the current, against the pressure of the depths, against the cold, murky waters of this dark world, and her mother did too, and whether it was their defiance or their stubbornness that saved them, it was enough to break them free of the whirlpool’s grasp.

Up and up they swam, shooting through the water like two seals, until they broke the surface, and the storm’s wind slapped their faces.

“Take her!” their mother cried, thrusting Ellen’s sleeping body into Aoife’s arms. “Don’t look back!”

Aoife barely had time to slip her arms under Ellen’s and hold her fast when their mother slipped down into the water again, disappearing as quick as a sinking rock.

The storm was still banging about, and the waves crested over Aoife’s head and came crashing down on her. If she wasn’t careful, the undertow would make their struggle all for naught. Her legs weak, and her chest stinging from exertion, she tried to swim to shore, but Ellen’s limp body was all dead weight. Aoife struggled, but huge gulps of seawater flooded into her mouth, and this time, the water did not taste like air. It burned harsher than before, and she choked and sputtered and felt herself losing the battle.

Then her feet felt a slimy pressure against them, and a push, like hands vaulting her over a wall, and a gentler wave came at just the same time, wafting her up and toward the shore. The momentum carried her forward, her legs finding renewed strength.

She and Ellen tumbled into the wet beach, foamy waves washing all around them. Aoife dragged her sister away from the tide, up the beachhead, and it was then that she saw the clam shell, buried under an entanglement of seaweed. Her fingers reached down into the slimy muck and pulled the shell free, the grit of the wet sand clinging to its pinkish surface. She wiped it as clean as she could with her wet hair.

Ellen’s eyes were closed, and though she still breathed, her chest only rose in shallow breaths, and her body was marked by shells and barnacles like the hull of an old ship.

Aoife held the shell upturned so that rainwater caught in its bowl. The pelts of rain were hard and scattered, but enough dribbled into the shell for one small sip. She held it to her sister’s mouth, and with a shaking hand, she pried open Ellen’s shell-encrusted lips. It was like breaking open the thin shell of a crab’s underbelly. She tilted the water into Ellen’s mouth until every last drop was gone, then she gathered more from the rain. The freshest, purest water she could find, she gave to her sister, making sure that her own tears didn’t mix in the bowl.

The spell had worked for Mother. It had even worked in some way for her. Now let it work for Ellen.

Aoife waited. It was the hardest waiting of all, the waiting for a life to be born. And as she waited, she couldn’t help but look to the sea, toward the horizon, hoping her mother would be there, coming to join them. But the waves rose and fell and swelled with the storm, and still, her mother was nowhere in sight.

Ellen’s mouth sucked in a breath as sharp as the wind. Her eyes fought against the crust of barnacles and tore themselves open. She gasped for air, her chest heaving.

Aoife cried out, joy and relief making tears spring to her eyes. She sobbed, and the tears fell all over Ellen, an endless sea of tears. Ellen started to sit up, and the two sisters found that now the barnacles flaked off her skin like dried sand. Together, they wiped away every last trace of the sea, but when she could stand again, Ellen’s eyes drifted toward the water.

“I thought I heard Mother’s voice…”

Aoife didn’t know what to say, so she said the truth. “Our Mother is a daughter of the sea.”

Ellen didn’t answer. She took hold of Aoife’s hand, and they both watched as the storm passed overhead and the pale sun crept out from behind distant clouds. Flecks of sunlight sparkled against the calming water. Aoife felt Ellen’s hand squeeze her own, and she knew why.

Far off, almost as close to the horizon as their eyes could see, a dark figure bobbed above the water. Just for an instant, nothing more, they saw the figure raise a webbed hand.

Then it was gone.

“Come,” said Aoife, her tears still kissing her cheeks. Hand in hand, she and her sister walked up the beach, back to dry land.

“Do you think, perhaps—” Ellen began as their feet hit the cobblestones of the village street.

“I don’t know,” Aoife answered. She knew the question Ellen was going to ask because it was her question too. “But we still have this.”

Holding up her other hand, she showed Ellen the clam shell nestled in the curve of her palm.

“The rain…” Ellen’s memory came back slowly. “I drank from it and…”

“Yes. Fresh this time.” Aoife grinned. “But salt the next.”

A New Collection and a Cover Reveal!

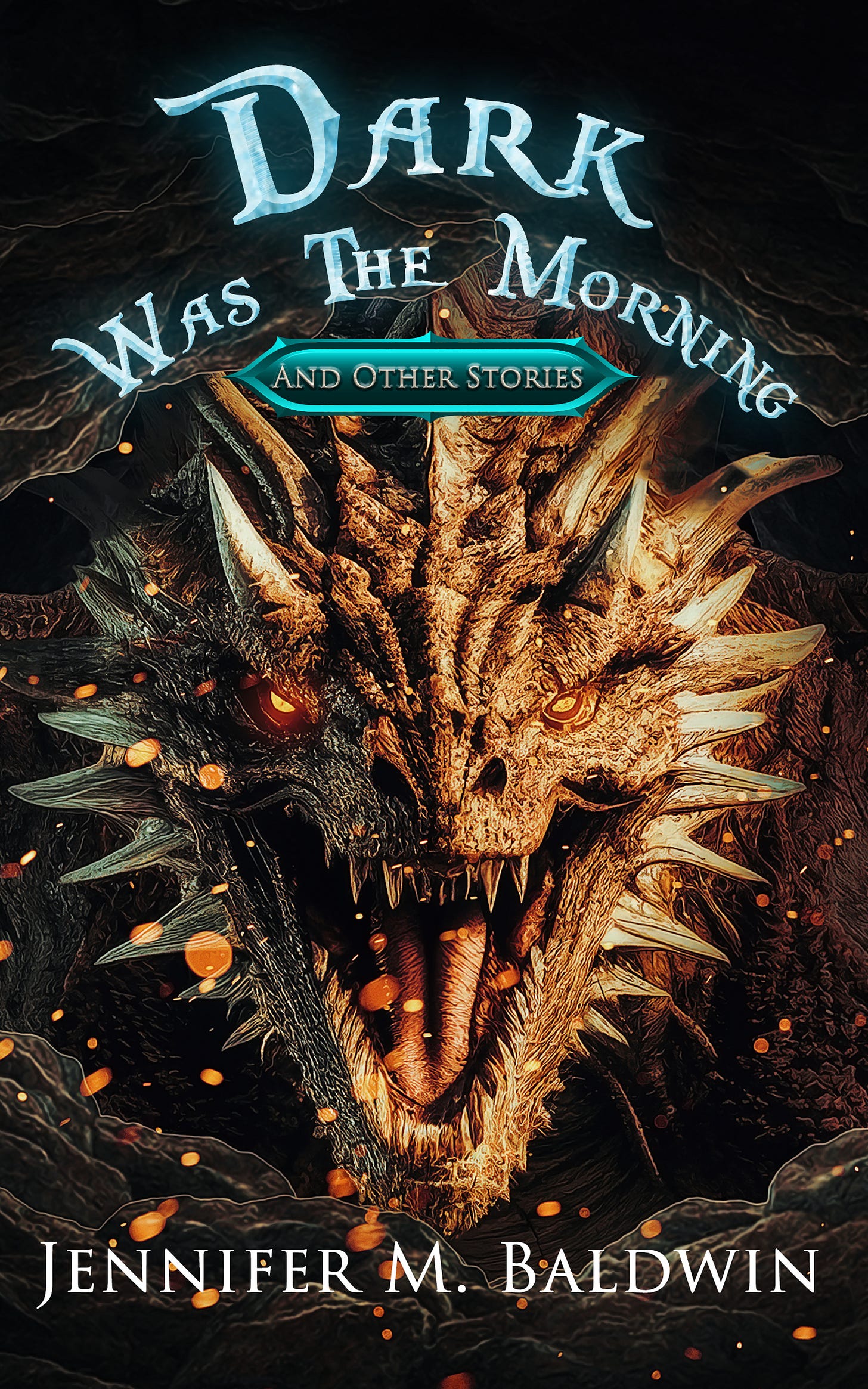

“Salt Kisses” is one of seven stories from my forthcoming collection, Dark Was the Morning and Other Stories, which is set to release this fall. I’m revealing the cover for the first time here:

And yes, one of the stories is about a dragon. Also included is a Merlin story that connects to my Merlin’s Last Magic series. It’s about Merlin’s time in Atlantis and involves one of the supporting characters from The Thirteen Treasures of Britain.

I’ll have more info about pre-ordering in the weeks to come.

That’s it for now! Thanks for reading! Please consider buying my books HERE, or my short stories HERE.

And if you enjoyed this post but can’t afford a monthly subscription, you can always buy me a coffee. Thank you!

Just finished the short story. Very stylistic! Enjoyed the read. 🙂

Gripping. Utterly gripping. I was compelled to read and read on until the story had passed. And now I am thinking only of the roiling sea.